tracing drift

Voices of Architecture

AHRA Research Student Symposium 2022

AHRA Research Student Symposium 2022

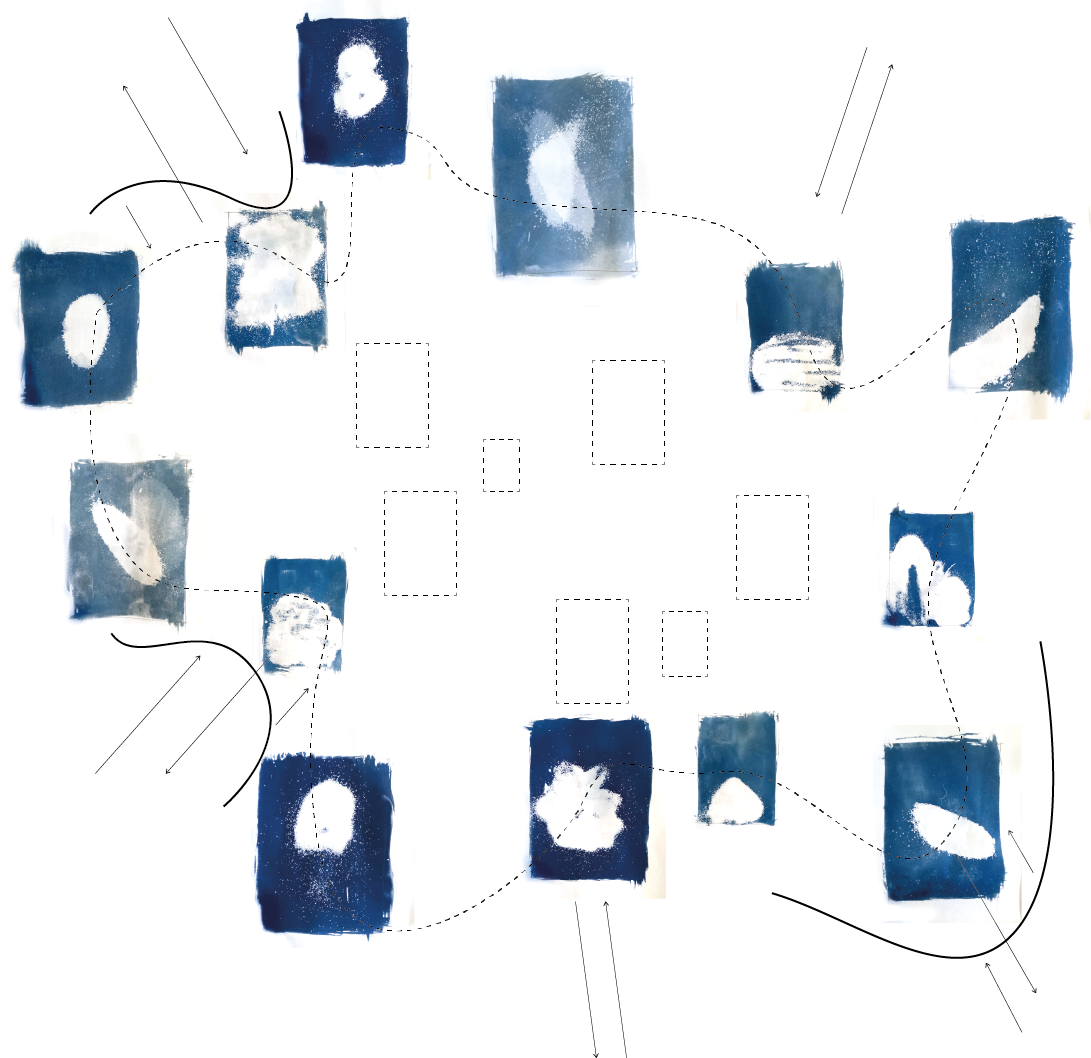

This piece of writing serves as a continuation of Perennial Drift, which is a study of Maltese landscapes of extraction and a speculation about possible futures for dust, a major by-product of stone extraction in Malta. This work serves as an attempt to showcase dust as a hyperobject, and using Timothy Morton’s notion of ‘form is memory’, cyanotype prints were developed to create traces of dust in motion.

The essay was presented at the AHRA Student Research Symposium at the University of Westminster, London, in April 2022, during which postgraduate students from across the world presented and discussed their ongoing research.

The essay was presented at the AHRA Student Research Symposium at the University of Westminster, London, in April 2022, during which postgraduate students from across the world presented and discussed their ongoing research.

April 2022 -

A few weeks ago, my front garden in London turned into a shade I’m familiar with back home in Malta, as it was coated in particles that have travelled thousands of kilometres across the Mediterranean Sea. Saharan dust made its way to London following a dust storm which was accelerated by Storm Celia in Spain. Malta is also prone to being hit by dust storms from the Sahara, but encountering it here in London continued to affirm the fact that particulate matter operates in a multitude of scales, with potentials which are far beyond what we can comprehend.

A few weeks ago, my front garden in London turned into a shade I’m familiar with back home in Malta, as it was coated in particles that have travelled thousands of kilometres across the Mediterranean Sea. Saharan dust made its way to London following a dust storm which was accelerated by Storm Celia in Spain. Malta is also prone to being hit by dust storms from the Sahara, but encountering it here in London continued to affirm the fact that particulate matter operates in a multitude of scales, with potentials which are far beyond what we can comprehend.

Extraction is not the only practice which contributes to the creation of dust. Process of dust release would still occur without us, with processes such as decay and erosion. All of these processes, however, drive an increasing amount of circulating dust in the atmosphere - as dust is launched into drift. As it takes flight, it is influenced by a new set of processes - the climatic and atmospheric, which can allow for the accumulation of dust flows which slowly imprint themselves onto surfaces of Earth, or on the surrounding sea bed. All of these are externalities, processes which do not belong within the material itself, but have a significant role in what dust becomes and how we interact with it.

Dust becomes an entity of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that it defeats notions of what it is in the first place - dust is a hyperobject. Once we are aware of its presence, such a being puts a significant strain on our normal ways of being and thinking.

Dust becomes an entity of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that it defeats notions of what it is in the first place - dust is a hyperobject. Once we are aware of its presence, such a being puts a significant strain on our normal ways of being and thinking.

With each cut we make, each blast, dust is released. Dust is a fraction of stone, a symbol of Maltese identity, therefore dust can also be seen as a unit of identity. Every speck of dust contains information about the whole - it may not directly be the material composition, but the properties, behaviour patterns, where it has been, where it is going.

Perhaps processes of extraction, which are continuously facilitating the production of dust and allowing it to launch into drift, will contribute to the creation of a new landscape, that which would have emerged as a result of human disruption. If this connection is legible, these landscapes/ landforms can serve as new monuments to the age of extraction, serving as testaments to the process that happened from years to eons ago; processes which were necessary for our species to survive, but may perhaps have escalated beyond our control.

Dust is a part of our landscape and a part of us. Long after we are gone, it will remain, keeping our voice within it.

The process (extraction) is what launches dust into drift. The instigator to the process. Dust becomes a material of agency, despite it being often overlooked or regarded as a nuisance or threat. It is a constituent of extraction which holds potential in the properties that define it - its ability to drift, it acting as a unit of information, a scaled down form of a unit of identity, its ability to travel and its ability to become. It is a condition present in all states of stone, the most fluid of extracts, undefined by the boundaries from which it emerges. It is a state present within each configuration of stone, waiting for the time to become. As stone is released from the earth, reconfigured, reused, and as it decays out of sight, the disembodying state of becoming dust is always present, as time is stretched and compressed along with it. At the liminal point of detachment from ground / stone / form, dust is neither here nor there, it holds information on where it has come from and also holds a potential to where it is going. It is an agent, linking material elements and processes together - what has created it, what has released it, what will influence what it will next become.

However, dust is never seen in entirety. Although it seems infinite, it is still a finite entity, but far too vast for us to comprehend. The parts that interact with us, visibly or not, are those which perhaps relate to us immediately, but they belong to a much greater entity. Our perception and opinion on dust is only one fragment of the whole. This means that the general itself can be compromised by the particular.

As Morton states - “Intelligence need not be thought of as having a picture of reality in the mind, but as an interaction between all kinds of entities that is somewhat ‘in the eye of the beholder’ ”.

However, dust is never seen in entirety. Although it seems infinite, it is still a finite entity, but far too vast for us to comprehend. The parts that interact with us, visibly or not, are those which perhaps relate to us immediately, but they belong to a much greater entity. Our perception and opinion on dust is only one fragment of the whole. This means that the general itself can be compromised by the particular.

As Morton states - “Intelligence need not be thought of as having a picture of reality in the mind, but as an interaction between all kinds of entities that is somewhat ‘in the eye of the beholder’ ”.

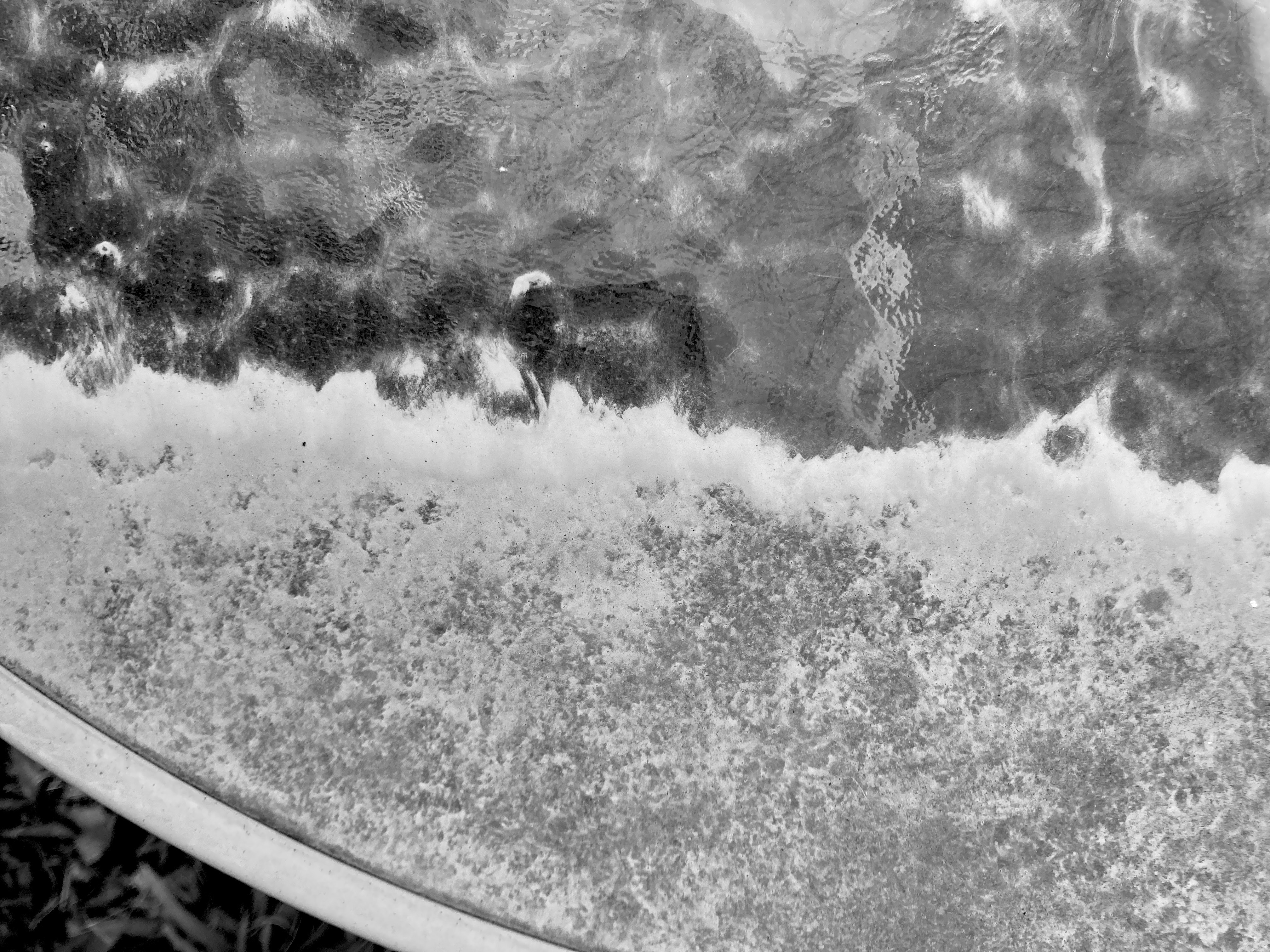

We become aware of it from the trace it leaves behind. When running our fingers along a bookshelf. An asthma attack. The buildup on pavement cracks. Dust reveals itself through its interaction with others, whether it is us, the weather, the elements, or time. In each situation, we become aware of it from the traces left behind through these interactions.

The traces that remain speak of conditions that are no longer actual. They become a record of the past. Form becomes memory, or memory becomes form. The trace is also a record of a possible state of dust, a possible form for it to have. Globigerina limestone formed as sediment was of a particular composition, planktonic carbonates, deposited in a particular depth, 200m, under minimal disruption. Who knows what it could have become otherwise? The traces left in my front garden were there cause of certain wind conditions, which allowed other fragments of dust to keep drifting, and those particular ones to remain intact, settled on my bike cover.

Dust acts as a boid - shifting fluidly. Influencing itself, but also influencing whatever’s around it. It has its own internal forces but also its externalities. What we see now is a current possible state, but there is a ridiculously large amount of other possibilities which could have emerged, which would have resulted in a completely different composition.

This way, the connection between the recorded instance and the body of possible instances would form a whole - enclosing time and opening out into time. The hyperobject becomes a body of possible, connected instances.

The traces that remain speak of conditions that are no longer actual. They become a record of the past. Form becomes memory, or memory becomes form. The trace is also a record of a possible state of dust, a possible form for it to have. Globigerina limestone formed as sediment was of a particular composition, planktonic carbonates, deposited in a particular depth, 200m, under minimal disruption. Who knows what it could have become otherwise? The traces left in my front garden were there cause of certain wind conditions, which allowed other fragments of dust to keep drifting, and those particular ones to remain intact, settled on my bike cover.

Dust acts as a boid - shifting fluidly. Influencing itself, but also influencing whatever’s around it. It has its own internal forces but also its externalities. What we see now is a current possible state, but there is a ridiculously large amount of other possibilities which could have emerged, which would have resulted in a completely different composition.

This way, the connection between the recorded instance and the body of possible instances would form a whole - enclosing time and opening out into time. The hyperobject becomes a body of possible, connected instances.

When talking about hyperobjects, Morton states that “Appearance is the past. Essence is the future. The strange strangeness of a hyperobject, its invisibility—it’s the future, somehow beamed into the ‘present.’ ”

Drifting processes over deep time have allowed planetary self-organisation to occur, however can these processes be further-altered or influenced on smaller, local contexts to achieve particular modes of organisation, such as material compositions, which can allow for certain levels of cultural meaning to emerge?

While Morton emphasises the fact that hyperobjects exist through their interactions with its surrounding entities, externalities which lie in between the two can equally be powerful as they have the potentials to manipulate perceptions and interactions between the two.

By understanding the value of dust and the potential it holds to create contextual forms of significance, we cannot resort to allowing ‘nature’ to displace and organise its own material in its own way. We need to question to what extent our drivers, as externalities, control the drifting dust, and start imagining what outcomes can emerge out of each iterative mechanism of control. A balance is needed for the constant negotiation between disruption and reclamation to take place - a negotiation between mitigating and producing habitat, slowing down and speeding up time and production.

Drifting processes over deep time have allowed planetary self-organisation to occur, however can these processes be further-altered or influenced on smaller, local contexts to achieve particular modes of organisation, such as material compositions, which can allow for certain levels of cultural meaning to emerge?

While Morton emphasises the fact that hyperobjects exist through their interactions with its surrounding entities, externalities which lie in between the two can equally be powerful as they have the potentials to manipulate perceptions and interactions between the two.

By understanding the value of dust and the potential it holds to create contextual forms of significance, we cannot resort to allowing ‘nature’ to displace and organise its own material in its own way. We need to question to what extent our drivers, as externalities, control the drifting dust, and start imagining what outcomes can emerge out of each iterative mechanism of control. A balance is needed for the constant negotiation between disruption and reclamation to take place - a negotiation between mitigating and producing habitat, slowing down and speeding up time and production.

Bibliography

Bridge, Gavin. “The Hole World: Scales and Spaces of Extraction.” Scenario Journal no. Extraction (2015). https://scenariojournal.com.

Cassar, JoAnn, Alex Torpiano, Tano Zammit, and Aaron Micallef. Proposal for the Nomination of Lower Globigerina Limestone of the Maltese Islands as a “Global Heritage Stone Resource” Scientific Research Publishing, Inc, 2017.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance.” In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Foster, Hal, 17-34. New York: New Press, 1998.

Hughes, Karel J. “Persistent Features from a Palaeo- Landscape: The Ancient Tracks of the Maltese Islands.” The Geographical Journal 165, no. 1 (1999): 62-78.

Kleinherenbrink, Arjen. Against Continuity : Gilles Deleuze’s Speculative Realism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Manaugh, Geoff, ed. Landscape Futures : Instruments, Devices and Architectural Interventions. New York: Actar, 2013.

Miodragovic Vella, Irina. “A Stereotomic Approach to Regional Digital Architecture.”University of Malta, 2019.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. doi:10.5749/j. ctt4cggm7.

Müller, Liana. “Landscapes of Memory: Interpreting and Presenting Places and Pasts.” In South African Landscape Architecture, edited by Hindes, Clinton, Hennie Stoffberg and Liana Müller, 7-26: Unisa Press, 2012.

Cassar, JoAnn, Alex Torpiano, Tano Zammit, and Aaron Micallef. Proposal for the Nomination of Lower Globigerina Limestone of the Maltese Islands as a “Global Heritage Stone Resource” Scientific Research Publishing, Inc, 2017.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance.” In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Foster, Hal, 17-34. New York: New Press, 1998.

Hughes, Karel J. “Persistent Features from a Palaeo- Landscape: The Ancient Tracks of the Maltese Islands.” The Geographical Journal 165, no. 1 (1999): 62-78.

Kleinherenbrink, Arjen. Against Continuity : Gilles Deleuze’s Speculative Realism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Manaugh, Geoff, ed. Landscape Futures : Instruments, Devices and Architectural Interventions. New York: Actar, 2013.

Miodragovic Vella, Irina. “A Stereotomic Approach to Regional Digital Architecture.”University of Malta, 2019.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. doi:10.5749/j. ctt4cggm7.

Müller, Liana. “Landscapes of Memory: Interpreting and Presenting Places and Pasts.” In South African Landscape Architecture, edited by Hindes, Clinton, Hennie Stoffberg and Liana Müller, 7-26: Unisa Press, 2012.

Pedley, H. M., M. R. House, and B. Waugh. “ The Geology of Malta and Gozo.” Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 27, no. 3 (1976): 325-341.

Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture without Architects : A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987.

Space Caviar, ed. Non-Extractive Architecture : On Designing without Depletion. Vol. 1. Berlin: Sternberg Press, V-AC Press, 2021.

Steyn, Stephen. “The Possession of Architecture.” . Accessed 5 December, 2021. https://counterspace- studio.com/writing/the-possession-of-architecture/? fbclid=IwAR3LY0QaH0MLX5KRo0SkxTHHsgoU8QH 9m78zs0j0NglZlXB_meMhtqO-P7k.

Szerszynski, Bronislaw. “Drift as a Planetary Phenomenon.” Performance Research 23, no. 7 (2018): 136-144.

The Malta Independent. “The Air our Children Breathe - the Dust and Pollution Silently Killing Us.” The Malta Independent, 18 May, 2019. https:// www.independent.com.mt/articles/2019-05-18/ newspaper-leader/TMID-Editorial-The-air-our- children-breathe-The-dust-and-pollution-silently- killing-us-6736208305.

Vally, Sumayya. “Ingesting Architectures: The Violence of Breathing in Parts of Joburg.” The Architectural Review no. 1482 (2021).

Vella, Alfred J. and Renato Camilleri. Fine Dust Emissions from Softstone Quarrying in Malta Malta Chamber of Scientists, 2005.

Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture without Architects : A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987.

Space Caviar, ed. Non-Extractive Architecture : On Designing without Depletion. Vol. 1. Berlin: Sternberg Press, V-AC Press, 2021.

Steyn, Stephen. “The Possession of Architecture.” . Accessed 5 December, 2021. https://counterspace- studio.com/writing/the-possession-of-architecture/? fbclid=IwAR3LY0QaH0MLX5KRo0SkxTHHsgoU8QH 9m78zs0j0NglZlXB_meMhtqO-P7k.

Szerszynski, Bronislaw. “Drift as a Planetary Phenomenon.” Performance Research 23, no. 7 (2018): 136-144.

The Malta Independent. “The Air our Children Breathe - the Dust and Pollution Silently Killing Us.” The Malta Independent, 18 May, 2019. https:// www.independent.com.mt/articles/2019-05-18/ newspaper-leader/TMID-Editorial-The-air-our- children-breathe-The-dust-and-pollution-silently- killing-us-6736208305.

Vally, Sumayya. “Ingesting Architectures: The Violence of Breathing in Parts of Joburg.” The Architectural Review no. 1482 (2021).

Vella, Alfred J. and Renato Camilleri. Fine Dust Emissions from Softstone Quarrying in Malta Malta Chamber of Scientists, 2005.