displace/define : an analysis of the formation of landscapes and the relationship between material extraction and cultural memory of the maltese civilisation

Theories of Critical Practices in Architecture

MA Architecture (Digital Media) 2021/22 (Distinction)

This essay aims to present extraction as a condition rooted in Maltese history, actively morphing landscape and simultaneously, cultural memory. Through the understanding of the term ‘landscape’ and our interaction with it, this essay acknowledges the intricate set of relationships present between the principles of nature, culture, form, memory and identity, and relates it to the process of extraction. The objective is not to assess the positive or negative impacts of the extraction of land, but to appreciate the meaning behind the process, through which that being extracted is transformed into architecture, with the remaining void acting as a visual testimony of the process, i.e. the eventual creation of an active monument.

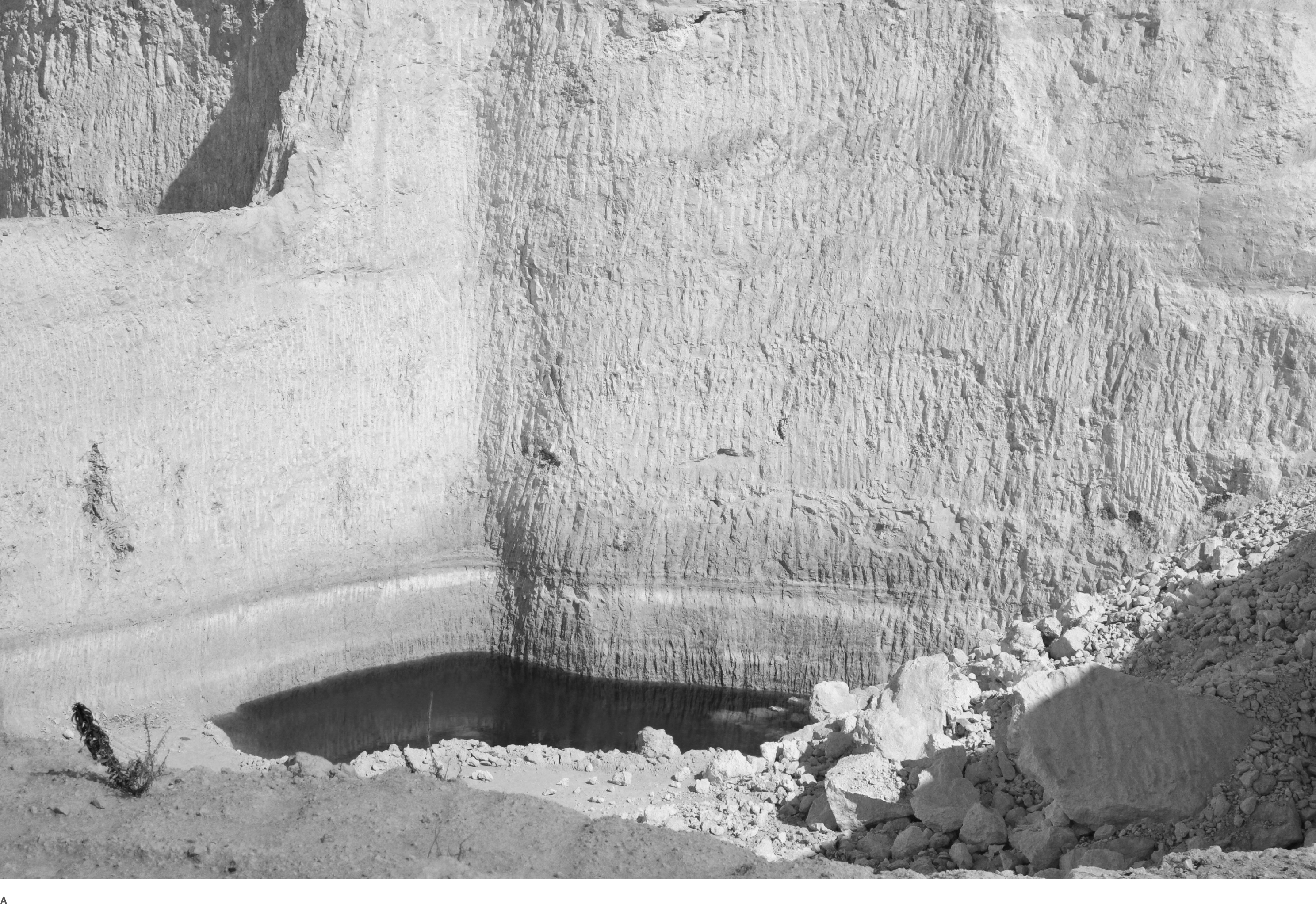

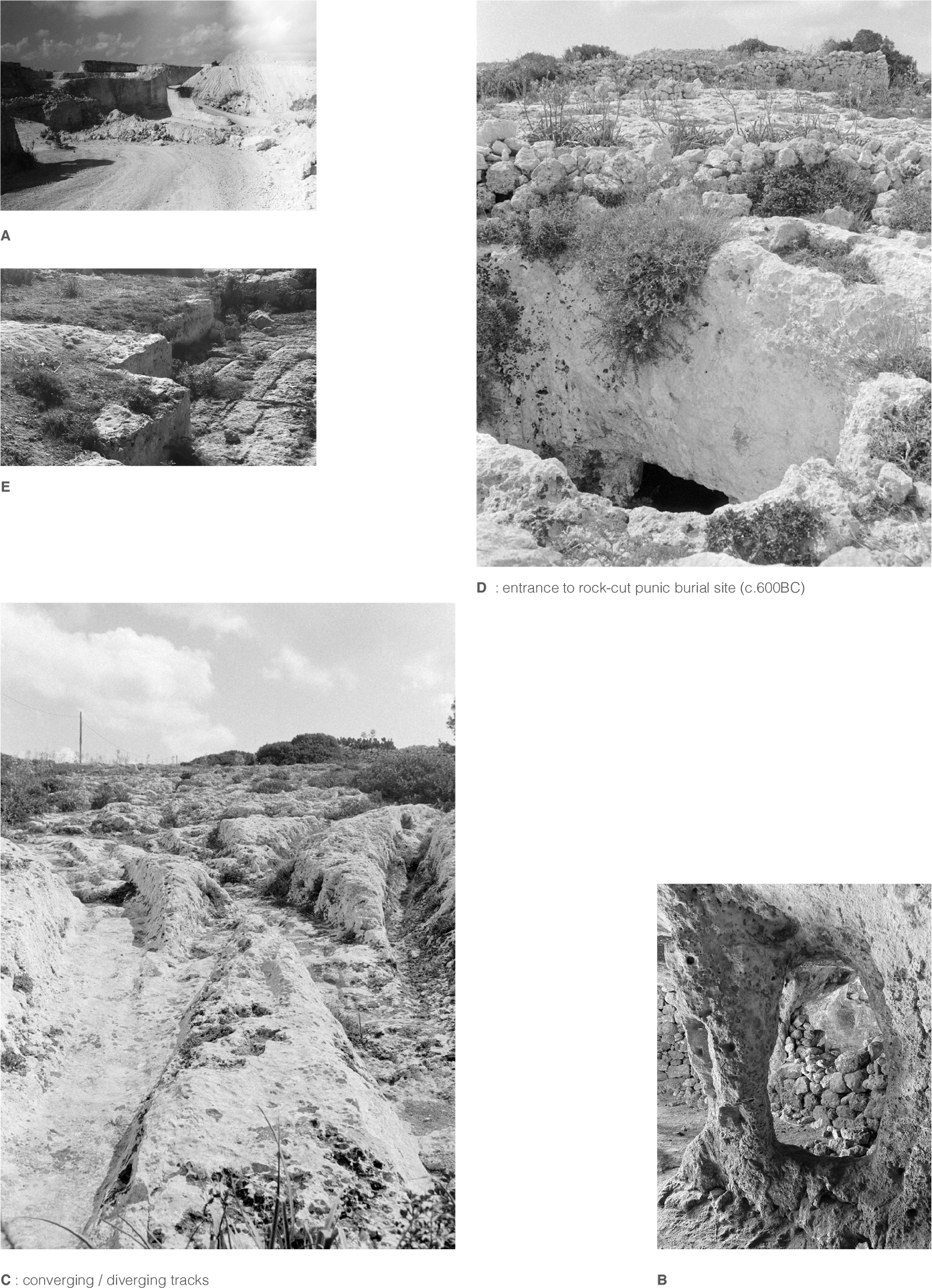

As an attempt to interpret the narrative at a regional scale, a particular site in the limits of Siggiewi, Malta, is studied: a site in which the Maltese civilisation’s relationship with the physicality of stone and the landscape can be observed through a multitude of forms from different periods of time (from the prehistoric cut to the contemporary large-scale quarry), all within a radius of less than a kilometre. This essay is largely supported by photographic work of this site, which runs in parallel with the narrative presented. This method of photography is vital, as it facilitates the pairing of production and representation as integral elements of what we define as landscape - as a term which arises from both visual and spatial practices.

As an attempt to interpret the narrative at a regional scale, a particular site in the limits of Siggiewi, Malta, is studied: a site in which the Maltese civilisation’s relationship with the physicality of stone and the landscape can be observed through a multitude of forms from different periods of time (from the prehistoric cut to the contemporary large-scale quarry), all within a radius of less than a kilometre. This essay is largely supported by photographic work of this site, which runs in parallel with the narrative presented. This method of photography is vital, as it facilitates the pairing of production and representation as integral elements of what we define as landscape - as a term which arises from both visual and spatial practices.

Definitions

‘Landscape’ is a layered term, the meaning of which has evolved over time. Although the initial, instinctive assimilation to the term would be that which constitutes natural landscapes, the word is derived from the Anglo- German term landscaef - which refers to a forest clearing for cattle, fields or huts, and therefore could be referred to as signifying a “unit of human occupation” (Schama, 1995). With the growing interest in nationalism and scientific progress of the nineteenth century, the term’s objective meaning was disassociated from civilisation and identified with the concept of pure nature - with references to the ultimate experience of wilderness being that of solitude in the wild, and with any kind of human intervention spoiling the image of the landscape (Taylor, 2008). The 20th century brought about a change in perception once more, with geographers Otto Schlüter, Franz Boas & Carl Sauer distinguishing between Urlandschaft (the original landscape) and Kulturlandschaft (the cultural landscape) (Sauer, 1938). As the adaptation of cultures according to the natural environment was observed and landscape morphology was seen a result of cultural intervention, the acknowledgement of the symbiosis of culture and landscape emerged. By the late 1990s, the notion of cultural landscapes made its way to cultural heritage management as UNESCO recognised several cultural landscapes as sites of outstanding universal value (Taylor, 2008).

Our interaction and occupation within the landscape can therefore be said to be crucial and should not be undermined, as it essentially comprises of a complex set of relationships, relating the principles of nature, culture, form, memory and identity. It is also the way we perceive this landscape which creates the distinction between raw materiality and landscape. Through our knowledge and observations, we can read landscape as a testament of time, with its layers filled with both natural and cultural values which inform the richness and depth of the place. Additionally, an understanding of activities, traditions and rituals that occur within a place, as well as the forms and symbols that emerge, continue to establish the abundance of cultural significance, as well as the emergence of valueswhich people assimilate to, which in turn create a sense of identity within which the formation of memory is afforded. This continues to demonstrate that both the physical and intangible correspond to the creation of sense of place, as well as the establishment of meaning associated with landscapes. They provide a framework for narration, be it that of an individual, a place or a community.

‘Landscape’ is a layered term, the meaning of which has evolved over time. Although the initial, instinctive assimilation to the term would be that which constitutes natural landscapes, the word is derived from the Anglo- German term landscaef - which refers to a forest clearing for cattle, fields or huts, and therefore could be referred to as signifying a “unit of human occupation” (Schama, 1995). With the growing interest in nationalism and scientific progress of the nineteenth century, the term’s objective meaning was disassociated from civilisation and identified with the concept of pure nature - with references to the ultimate experience of wilderness being that of solitude in the wild, and with any kind of human intervention spoiling the image of the landscape (Taylor, 2008). The 20th century brought about a change in perception once more, with geographers Otto Schlüter, Franz Boas & Carl Sauer distinguishing between Urlandschaft (the original landscape) and Kulturlandschaft (the cultural landscape) (Sauer, 1938). As the adaptation of cultures according to the natural environment was observed and landscape morphology was seen a result of cultural intervention, the acknowledgement of the symbiosis of culture and landscape emerged. By the late 1990s, the notion of cultural landscapes made its way to cultural heritage management as UNESCO recognised several cultural landscapes as sites of outstanding universal value (Taylor, 2008).

Our interaction and occupation within the landscape can therefore be said to be crucial and should not be undermined, as it essentially comprises of a complex set of relationships, relating the principles of nature, culture, form, memory and identity. It is also the way we perceive this landscape which creates the distinction between raw materiality and landscape. Through our knowledge and observations, we can read landscape as a testament of time, with its layers filled with both natural and cultural values which inform the richness and depth of the place. Additionally, an understanding of activities, traditions and rituals that occur within a place, as well as the forms and symbols that emerge, continue to establish the abundance of cultural significance, as well as the emergence of valueswhich people assimilate to, which in turn create a sense of identity within which the formation of memory is afforded. This continues to demonstrate that both the physical and intangible correspond to the creation of sense of place, as well as the establishment of meaning associated with landscapes. They provide a framework for narration, be it that of an individual, a place or a community.

Memory emerges out of meaning. It can be said to be a process which continuously constructs the past, and is dependent on numerous personal and social conditions (Holtorf, 2000, cited in Müller, 2012). Therefore memory should not be simply regarded as an act of recalling figures and events, but rather a complex process of negotiation over what is remembered and what is erased. This allows for the constant reconstruction and reinterpretation of the past. Personal memory is an incremental part of a collective process, which is shaped by norms, ideologies, and the collective identity of a society. Nevertheless, personal memories are interwoven with those of society, and are never isolated. They are related to the individual’s past and present conditions, but also to that of the society he/she belongs to. Memory defines the sense of self of individuals and societies.

One can therefore define collective memory as the constructed perception of the past based on consented versions of previous events, by a social group (Halbwachs, 1939, cited in Müller, 2012). Through the concept of collective memory, emerges cultural memory, which Jan Assmann defined as the “process whereby a society preserves its collective knowledge between generations through cultural mnemonics. Cultural memory may be seen as the collective constructions of the past to aid future generations in establishing and maintaining their cultural identity.” (Assmann, 1992, cited in Müller, 2012). As memories are passed down from one generation to the next, the fragments constituting collective identity are bound to evolve and change, reconstructing cultural identity. However, as a shared past is created and awareness of the unity of identities is reinforced, the concept of collective identity persists.

One can therefore define collective memory as the constructed perception of the past based on consented versions of previous events, by a social group (Halbwachs, 1939, cited in Müller, 2012). Through the concept of collective memory, emerges cultural memory, which Jan Assmann defined as the “process whereby a society preserves its collective knowledge between generations through cultural mnemonics. Cultural memory may be seen as the collective constructions of the past to aid future generations in establishing and maintaining their cultural identity.” (Assmann, 1992, cited in Müller, 2012). As memories are passed down from one generation to the next, the fragments constituting collective identity are bound to evolve and change, reconstructing cultural identity. However, as a shared past is created and awareness of the unity of identities is reinforced, the concept of collective identity persists.

Landscape can be said to be a “physical manifestation of a culture’s understanding of its past and future” (Kuchler,1993 , cited in Müller, 2012), which therefore strengthens a society’s cultural identity. Although the legibility of a landscape may seem to be clear, even to those who do not necessarily belong to it, there are always intangible layers of significance which present themselves only to a few, which implies that the perception and reaction to a landscape is not always coherent or universal. The landscape’s image can be said to be perceived and interacted with by a viewer who has been moulded and shaped from his/her/their physical, mental and social background. Therefore, changing perceptions and concepts of beings are a part of the change of landscapes. This continues to strengthen the argument of landscapes not simply serving as symbolic backdrops, but of having the capability of performing instrumental roles in the culture and development of society. In Emerging Landscapes, Derieu and Kamvasinou sought to explore the specific relationship between production and representation of landscapes, with production being the series of processes involved in the physical transformation of the land, and representation referring to the ways in which meaning arises from these environments, and how this is expressed. They argue that since the beginning of the twenty-first century, dramatic changes have occurred in culture, technology and economy which have directly influenced the earth’s surface. Through these transformations, changes also came about in methods of representation, which in turn influenced the way landscapes are perceived and reflected in our environment, our architecture and our culture (Deriu et al., 2014).

The legacy of certain cultural elements calls for tangible manifestations which memories can latch onto. These may be forms, structures or methods of representation, all of which may allow an individual or a group of people to make assimilations and create relationships between the physical and the intangible throughout different periods of time. Meaning is often evoked in liminal spaces, which can be defined as “spaces between disciplines or at the threshold of the senses” (Müller, 2012). The site being studied in this essay provides a perfect setting for this manifestation of cultural memory, as through its multiple layers, it demonstrates the way a particular process evolved over time, and how this process and the meaning assimilated with it has been reflected in the landscape. The process being referred to is that of stone extraction.

The legacy of certain cultural elements calls for tangible manifestations which memories can latch onto. These may be forms, structures or methods of representation, all of which may allow an individual or a group of people to make assimilations and create relationships between the physical and the intangible throughout different periods of time. Meaning is often evoked in liminal spaces, which can be defined as “spaces between disciplines or at the threshold of the senses” (Müller, 2012). The site being studied in this essay provides a perfect setting for this manifestation of cultural memory, as through its multiple layers, it demonstrates the way a particular process evolved over time, and how this process and the meaning assimilated with it has been reflected in the landscape. The process being referred to is that of stone extraction.

Extraction

Extraction can be defined as the activity by which a condition or a material is withdrawn from its original environment, in order to redefine its function. Therefore, it cannot be thought of as an isolated activity, but rather as a process characterised by displacement and transformation. However, it is also important to note that two main protagonists belong to the process; the extract and the remnant. In the case of stone extraction, this refers to the raw material which is being displaced from the earth, and the void which remains. The intent behind the process may either be to make use of that which is being extracted, or to transform that void. In either case, a trace of the process is always left behind. With stone being such an integral part of the Maltese natural landscape, it is inevitable to notice that the extractive process actively transforms the island’s natural landscape, however we can now acknowledge the fact that this process also transforms the culture that is shaped by it and around it. It is undeniable that stone has a complex geological language of its own, however the cultural language and significance that it offers is one which is just as intricate, as it evolves over time through its different purposes. Perhaps it can be said that there exists a third protagonist belonging to extraction: the force which drives the process. This would consist of the condition which leads to extraction (be it physical or intangible), the mechanism by which extraction takes place, and also the meaning that emerges.

As Hugh suggests, the power of island landscapes (although now verging on becoming nonexistent through globalisation) lies in the physical isolation of societies which allows the cultivation of distinct cultures with unique perceptions expressed in the landscape. Throughout history, a number of culturally significant characteristics emerged as remnants of the interaction between society and the raw material available, which persist as reflections of a rich cultural heritage in a transformed landscape (Hughes, 1999). The way extraction has been reflected in the Maltese landscape can be seen as a pure result of this. These remnants take shape either through the extracted material or the void, however the driving cultural force behind each is always present.

Extraction can be defined as the activity by which a condition or a material is withdrawn from its original environment, in order to redefine its function. Therefore, it cannot be thought of as an isolated activity, but rather as a process characterised by displacement and transformation. However, it is also important to note that two main protagonists belong to the process; the extract and the remnant. In the case of stone extraction, this refers to the raw material which is being displaced from the earth, and the void which remains. The intent behind the process may either be to make use of that which is being extracted, or to transform that void. In either case, a trace of the process is always left behind. With stone being such an integral part of the Maltese natural landscape, it is inevitable to notice that the extractive process actively transforms the island’s natural landscape, however we can now acknowledge the fact that this process also transforms the culture that is shaped by it and around it. It is undeniable that stone has a complex geological language of its own, however the cultural language and significance that it offers is one which is just as intricate, as it evolves over time through its different purposes. Perhaps it can be said that there exists a third protagonist belonging to extraction: the force which drives the process. This would consist of the condition which leads to extraction (be it physical or intangible), the mechanism by which extraction takes place, and also the meaning that emerges.

As Hugh suggests, the power of island landscapes (although now verging on becoming nonexistent through globalisation) lies in the physical isolation of societies which allows the cultivation of distinct cultures with unique perceptions expressed in the landscape. Throughout history, a number of culturally significant characteristics emerged as remnants of the interaction between society and the raw material available, which persist as reflections of a rich cultural heritage in a transformed landscape (Hughes, 1999). The way extraction has been reflected in the Maltese landscape can be seen as a pure result of this. These remnants take shape either through the extracted material or the void, however the driving cultural force behind each is always present.

The Transformed Extract

Malta has been an island shaped by changing influences and fixed materiality. Up until fifty years ago, Maltese architecture could be defined as displaced landscape. The primitive hut formed out of rubble and the megalithic temples erected were the foundations for the complex stereotomy which followed. As building typologies became more complex throughout the ages - from complex arched vaults to baroque palaces adorned with carvings and embellishments - the use of Maltese stone and the development of its affordancepersisted. With the direct action of cutting and building, stone was given meaning through its placement, defining a landscape with settlements undulating across the terrain, making the built and unbuilt one and the same.

As architecture is inhabited, meaning is instinctively associated by the personal user. However, as a typology grows in popularity and becomes a cultural symbol, collective memory starts to emerge and the relationship between culture and landscape becomes evident. The tactility and the materiality of stone also holds a lot of potential for meaning - its sensory invitation and its depth offers timelessness through its authenticity. The way it ages and changes over time is purely the inverse of an artificial condition negating theconcept of time. Stone can be said to invoke liminal spaces through a haptic architecture - “It seeks to accommodate rather than impress, evoke domesticity and comfort rather than admiration and awe” (Pallasmaa, 2000).

Through advancements in technology and the growing desire for a globalised world, the possibility of new materialities and a change in values brought about a change in the way the built environment is perceived, and the primary use of Maltese hardstone started to be as an agent in the production of concrete, therefore becoming a ‘secondary’ material. Therefore it cannot be read in its entirety through its architecture, rather the scale of the void left behind can be seen as a testament much more true to its being.

Malta has been an island shaped by changing influences and fixed materiality. Up until fifty years ago, Maltese architecture could be defined as displaced landscape. The primitive hut formed out of rubble and the megalithic temples erected were the foundations for the complex stereotomy which followed. As building typologies became more complex throughout the ages - from complex arched vaults to baroque palaces adorned with carvings and embellishments - the use of Maltese stone and the development of its affordancepersisted. With the direct action of cutting and building, stone was given meaning through its placement, defining a landscape with settlements undulating across the terrain, making the built and unbuilt one and the same.

As architecture is inhabited, meaning is instinctively associated by the personal user. However, as a typology grows in popularity and becomes a cultural symbol, collective memory starts to emerge and the relationship between culture and landscape becomes evident. The tactility and the materiality of stone also holds a lot of potential for meaning - its sensory invitation and its depth offers timelessness through its authenticity. The way it ages and changes over time is purely the inverse of an artificial condition negating theconcept of time. Stone can be said to invoke liminal spaces through a haptic architecture - “It seeks to accommodate rather than impress, evoke domesticity and comfort rather than admiration and awe” (Pallasmaa, 2000).

Through advancements in technology and the growing desire for a globalised world, the possibility of new materialities and a change in values brought about a change in the way the built environment is perceived, and the primary use of Maltese hardstone started to be as an agent in the production of concrete, therefore becoming a ‘secondary’ material. Therefore it cannot be read in its entirety through its architecture, rather the scale of the void left behind can be seen as a testament much more true to its being.

The Cut That Remains

Extractive landscapes can also be said to be defined by their own absence. As the surface of earth is punctured, the negative space created through the void can be infinitely interpreted. Cuts in the stone present in the Maltese landscapes vary in typology, as they range from the hand cut symbol to the contemporary quarry. Despite the range of scales, meaning could still be identified in all of them.

As stone is repeatedly extracted through the same process in the name of creation, the typology of the quarry emerges. Quarries can be seen as altered landscapes but also as monuments - they lie at intersection of landscape, geology, technology, and culture, and their stories remain accessible through the visual testimony of the land, as well as the stories of the buildings built from them. Given the scale of the island, the void and its product remain in close proximity, therefore the association between the two remains tangible. From the historic quarry to the large-scale contemporary one, the different modes of extraction for different kinds of outputs give rise to varying forms of quarries - from the precise cuts arising from ashlar stone quarrying to the haphazard volumes of blast-driven quarries for stone aggregates. Despite these different outcomes, the seemingly extra-terrestrial terrain of any kind of quarry often renders the landscape sublime. The question lies whether one can assimilate meaning through the form of the quarry with current cultural conversations. As the scale of contemporary quarries grows exponentially according to rising demands of the construction industry, they serve as a record of that which has been extracted from nature to serve the growth of a society - be it in the name of culture or economy.

The creation of voids for infrastructural reasons should also be considered. The enigmatic cart ruts, which are presumed to be of late-prehistoric age (Hughes, 1999), can be seen as one of humanity’s earliest infrastructural creations and have persisted for thousands of years. There have been numerous theories regarding what their potential purpose might have been (whether as agricultural water channels or tracks for some kind of cart typology, or quarrying itself) and how they were created by man, yet the fact that they were created to establish some form of relationship between one site or another through the incision of stone shows the way cultures have always interacted with the natural landscape to develop and create new meanings. These incisions also demonstrate their authenticity as relics in cultural landscapes through their physical survival as the prime source of evidence in the geology (Magro Conti and Saliba, 2005).

Voids have also found meaning though occupation. The natural sheltered form of a cave could be regarded as one of the earliest forms of habitation for civilisation, but throughout Maltese history, the natural feature was also exploited though extensive carving to extend human occupation, as cave dwelling developed. Through a similar approach as the cart ruts, cultures continued to exploit properties of stone within caves in order to create new forms of infrastructure within it, from cooking hearths, to throughs for cattle, to sleeping bunks. However, the fact that the stone was able to provide shelter and a home for civilisation, this mode of occupation also became a storehouse of collective memory, as troglodytes found home and meaning literally within the natural landscape.

The symbolic characteristics found in stone should also not be undermined. As people make carvings in stone, whether commemorative, spiritual or decorative, the intent embodies the idea of permanence. Although practical reasons may also be considered, the symbolic reference can also extend to underground burial rituals that have been a common mode of practice, ranging from Punic tombs, to Christian catacombs, where a space for refuge is offered for passing over, and also for the performance of rituals and ceremonies (Weston, 2015).

Extractive landscapes can also be said to be defined by their own absence. As the surface of earth is punctured, the negative space created through the void can be infinitely interpreted. Cuts in the stone present in the Maltese landscapes vary in typology, as they range from the hand cut symbol to the contemporary quarry. Despite the range of scales, meaning could still be identified in all of them.

As stone is repeatedly extracted through the same process in the name of creation, the typology of the quarry emerges. Quarries can be seen as altered landscapes but also as monuments - they lie at intersection of landscape, geology, technology, and culture, and their stories remain accessible through the visual testimony of the land, as well as the stories of the buildings built from them. Given the scale of the island, the void and its product remain in close proximity, therefore the association between the two remains tangible. From the historic quarry to the large-scale contemporary one, the different modes of extraction for different kinds of outputs give rise to varying forms of quarries - from the precise cuts arising from ashlar stone quarrying to the haphazard volumes of blast-driven quarries for stone aggregates. Despite these different outcomes, the seemingly extra-terrestrial terrain of any kind of quarry often renders the landscape sublime. The question lies whether one can assimilate meaning through the form of the quarry with current cultural conversations. As the scale of contemporary quarries grows exponentially according to rising demands of the construction industry, they serve as a record of that which has been extracted from nature to serve the growth of a society - be it in the name of culture or economy.

The creation of voids for infrastructural reasons should also be considered. The enigmatic cart ruts, which are presumed to be of late-prehistoric age (Hughes, 1999), can be seen as one of humanity’s earliest infrastructural creations and have persisted for thousands of years. There have been numerous theories regarding what their potential purpose might have been (whether as agricultural water channels or tracks for some kind of cart typology, or quarrying itself) and how they were created by man, yet the fact that they were created to establish some form of relationship between one site or another through the incision of stone shows the way cultures have always interacted with the natural landscape to develop and create new meanings. These incisions also demonstrate their authenticity as relics in cultural landscapes through their physical survival as the prime source of evidence in the geology (Magro Conti and Saliba, 2005).

Voids have also found meaning though occupation. The natural sheltered form of a cave could be regarded as one of the earliest forms of habitation for civilisation, but throughout Maltese history, the natural feature was also exploited though extensive carving to extend human occupation, as cave dwelling developed. Through a similar approach as the cart ruts, cultures continued to exploit properties of stone within caves in order to create new forms of infrastructure within it, from cooking hearths, to throughs for cattle, to sleeping bunks. However, the fact that the stone was able to provide shelter and a home for civilisation, this mode of occupation also became a storehouse of collective memory, as troglodytes found home and meaning literally within the natural landscape.

The symbolic characteristics found in stone should also not be undermined. As people make carvings in stone, whether commemorative, spiritual or decorative, the intent embodies the idea of permanence. Although practical reasons may also be considered, the symbolic reference can also extend to underground burial rituals that have been a common mode of practice, ranging from Punic tombs, to Christian catacombs, where a space for refuge is offered for passing over, and also for the performance of rituals and ceremonies (Weston, 2015).

The essence of these features in the landscape is in the narrative they present, and through the memory and cultural meaning instilled in them, they can be therefore seen as monuments. They serve as active monuments which do not necessarily freeze the concept of time and dictate a particular story, but allow varying degrees of interpretation and perception. Through the unformalised layers of presentation of this extractive landscape, multiple stories of collective memory are illustrated. This landscape is authentic in a way that it does not contest the reality of past and present culture, but rather reveals the complexity of it and how it has evolved over time. It can be seen as an excavation on its own, revealing the levels of stories and memories that lie beneath the surface, allowing for the constant reconstruction and reinterpretation of the past.

This essay aims to serve as a tool for reflection on the importance of the materiality of stone in the Maltese culture’s narrative, as well as the crucial role of the products of the interaction between culture and the natural landscape. These products - the extract and the void - have the power to illustrate certain levels of authenticity and meaning in surrounding contexts as they are intrinsically agents to a culture’s legacy. The cultural and economic shifts of the last few decades have brought about changes in perspectives and values, and the increasing reliance on remotely extracted resources challenges this relationship between site and culture. Meanwhile, the use of Maltese stone has started to gain acknowledgement and recognition, as Globigerina Limestone has been granted designation of a Global Heritage Stone Resource (Times of Malta, 2019). Given the relationships established between nature, identity, memory which have been acknowledged in this essay, a number of questions arise when analysing these changes;

What could happen should the current construction industry become redundant, when we have over-extracted our resource - what meaning will we find then? Is it possible to find meaning and establish a collective, cultural identity through that which has been imported? How will culture evolve, and what will be extracted? Can stone afford this change, and will its use persist, or will it just serve as an agent for nostalgia? Will the void retain its monumentality when that which has been extracted can no longer be read?

What could happen should the current construction industry become redundant, when we have over-extracted our resource - what meaning will we find then? Is it possible to find meaning and establish a collective, cultural identity through that which has been imported? How will culture evolve, and what will be extracted? Can stone afford this change, and will its use persist, or will it just serve as an agent for nostalgia? Will the void retain its monumentality when that which has been extracted can no longer be read?

Bibliography

Bastéa, E. (2004). What Memory? Whose Memory? Memory and Architecture. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 283-291.

Buhagiar, K. (2017). Investigating cave dwelling in medieval Malta (AD 800–1530), 1st ed. Oxbow Books.

Carlisle, S. and Pevzner Nicholas (2015). Introduction: Extraction. Scenario Journal. Available from: https:// scenariojournal.com/article/introduction-extraction/ [Accessed08/03/2021].

Deriu, D., Kamvasinou, K., Shinkle, E. (2014). Emerging landscapes : between production and representation. Farnhan Surrey, England ;: Ashgate Publishing.

Hughes, K.J. (1999). Persistent Features from a Palaeo- Landscape: The Ancient Tracks of the Maltese Islands. The Geographical Journal. 165 (1), 62-78.

Magro Conti, J. and Saliba, P.C. (2005). The significance of cart-ruts in ancient landscapes. Midsea Books.

Mottershead, D., Pearson, A., Farres, P., Schaefer, M. (2019). Humans as Agents of Geomorphological Change: The Case of the Maltese Cart-Ruts at Misraħ Għar Il-Kbir, San Ġwann, San Pawl Tat-Tarġa and Imtaħleb, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Mottershead, D., Pearson, A., Schaefer, M. (2008). The cart ruts of Malta: an applied geomorphology approach. Antiquity. 82 (318), 1065-1079.

Buhagiar, K. (2017). Investigating cave dwelling in medieval Malta (AD 800–1530), 1st ed. Oxbow Books.

Carlisle, S. and Pevzner Nicholas (2015). Introduction: Extraction. Scenario Journal. Available from: https:// scenariojournal.com/article/introduction-extraction/ [Accessed08/03/2021].

Deriu, D., Kamvasinou, K., Shinkle, E. (2014). Emerging landscapes : between production and representation. Farnhan Surrey, England ;: Ashgate Publishing.

Hughes, K.J. (1999). Persistent Features from a Palaeo- Landscape: The Ancient Tracks of the Maltese Islands. The Geographical Journal. 165 (1), 62-78.

Magro Conti, J. and Saliba, P.C. (2005). The significance of cart-ruts in ancient landscapes. Midsea Books.

Mottershead, D., Pearson, A., Farres, P., Schaefer, M. (2019). Humans as Agents of Geomorphological Change: The Case of the Maltese Cart-Ruts at Misraħ Għar Il-Kbir, San Ġwann, San Pawl Tat-Tarġa and Imtaħleb, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Mottershead, D., Pearson, A., Schaefer, M. (2008). The cart ruts of Malta: an applied geomorphology approach. Antiquity. 82 (318), 1065-1079.

Müller, L. (2012). Landscapes of Memory: Interpreting and Presenting Places and Pasts. In: Hindes, C., Stoffberg, H., Müller, L., (eds.) South African landscape architecture. Unisa Press, 7-26.

Pallasmaa, J. (2000). Hapticity and Time. The Architectural Review. (207), 78-84.

Psarra, S. (2009). The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning. Architecture and narrative the formation of space and cultural meaning. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ;: Routledge, 233-250.

Sagona, C. (2004). Land use in prehistoric Malta. A re‐ examination of the Maltese ‘cart ruts’. Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 23 (1), 45-60.

Sauer, C.O. (1938). The morphology of landscape . Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and memory. London: HarperCollins.

Stedman, R.C. (2003). Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society & Natural Resources. 8 (16), 671-685.

Taylor, K. (2008). Landscape and memory. Proceedings of the 3rd International Memory of the World Conference.19-22.

Times of Malta (2019). Globigerina limestone receives global recognition. Times of Malta. Jan 16.

Weston, G.E. (2015). Clapham Junction : 3000 years of Maltese Heritage.

Pallasmaa, J. (2000). Hapticity and Time. The Architectural Review. (207), 78-84.

Psarra, S. (2009). The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning. Architecture and narrative the formation of space and cultural meaning. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ;: Routledge, 233-250.

Sagona, C. (2004). Land use in prehistoric Malta. A re‐ examination of the Maltese ‘cart ruts’. Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 23 (1), 45-60.

Sauer, C.O. (1938). The morphology of landscape . Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and memory. London: HarperCollins.

Stedman, R.C. (2003). Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society & Natural Resources. 8 (16), 671-685.

Taylor, K. (2008). Landscape and memory. Proceedings of the 3rd International Memory of the World Conference.19-22.

Times of Malta (2019). Globigerina limestone receives global recognition. Times of Malta. Jan 16.

Weston, G.E. (2015). Clapham Junction : 3000 years of Maltese Heritage.